A shell — that’s how brain injury felt. Cracked open and discarded: the very heart of me, a flickering sign of vacancy.

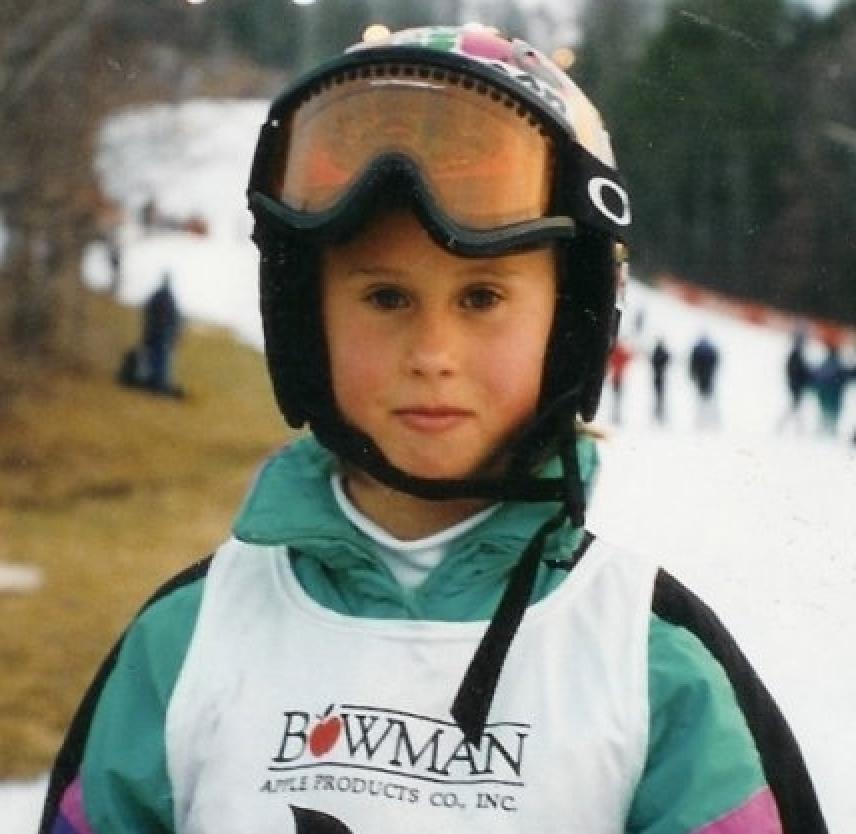

There was no single blow to the head. I lost consciousness once, briefly. But there were many blows, and the athlete in me kept pushing to reach my goals. I’m a stubborn person. When I was told at age twelve I’d never accomplish my dream of becoming an Olympic ski racer because I was from Virginia, I couldn’t swallow the odds stacked up against me. I persisted, through anything, even brain injury.

We all make mistakes and we learn from them. We shouldn’t regret our mistakes, but rather, use them as tools. Mistakes lead us to new opportunity. I guess that’s true in a way: as a graduating senior, I was on track to attend Bates College, but the US Ski Team named me to their development program. Two years later, a version of myself was accepted at the University of Colorado at Boulder. And there, I met Dr. James Kelly, a neurologist at the University of Colorado Hospital.

But I’ll come back to those details in a minute.

I regret my mistakes. As an athlete, I responded to the pressure applied, flattening my opportunity and fractioning my own potential by ignoring the risks. Concussion after concussion, I continued competing until the helmet cracked in half and fell off my head. To be fair, brain injury wasn’t a national headline at the time. My coaches and parents were aware of it, but if the headache was gone, I was clear to compete.

And then the headache never went away. Like a dense fog, flipping my world in a fit of vertigo, I could barely find my own feet. I quickly failed on skis, crashing through safety nets, breaking my leg, tearing ligaments in my knee, and hitting my head once again. I nearly broke my neck trying to retain my spot on the US Development Team, and it was in that moment, as I lay in the snow, the blood dripping off my face, my helmet cracked in half on the ground next to me, and my ski hanging in the safety net fifteen feet above me, that I quit ski racing.

But this relief from the outside pressure was a crash too late. I stuttered and stumbled over words. My skin became pale, clammy, and unfamiliar. My heart pounded and chest pains left me struggling for breath. The muscle on my left side eroded. My head throbbed each afternoon. My temper raged as a depression buried me.

As clear as it is now, at the time, brain injury was not the obvious answer. I had sustained concussions throughout my career, but linking several symptoms to a six year span of injuries was not a rational connection to the irrational disconnect in my body. I was dubbed a hypochondriac, a self-fulfilling prophecy, and at the end of the day, a failure.

These sentiments drove me thousands of miles away, to the University of Colorado at Boulder, where as a college freshman the higher elevation quickly exacerbated my symptoms. A routine doctor’s visit led me to a cardiologist, who led me to neurologist Dr. James Kelly. He sifted through the fog and extracted the cause: nerve damage restricting important functions of the heart, the eyes, and the left side of my body.

During the years immediately following the diagnosis, very little changed for me. Some symptoms were alleviated, but the physical erosion made me feel like a shell. The knowledge of nerve damage didn’t arm me with an immediate path to recovery. And that’s what makes brain injury the very difficult riddle that it is: it isn’t logical or consistent. Like determining the order of trees in a forest, life passed in a very confusing, cluttered, and dark way. There was no easy road to open ground.

Equilibrium is a sense I’ve regained in the seven years since the diagnosis. The shell-like feeling dissolved as I began balancing on two feet again, learning new ideas, and connecting opposing ideas. Most of my symptoms were less cognitive in nature to begin with, but frustration and anger were secondary symptoms that hung over me like a fog, blocking my cognitive progress. As I learned to manage my physical symptoms — tachycardia that leaves me with a sinking fatigue, a left eye that doesn’t track left-to-right and causes migraines, and a weakened left side that I occasionally trip over — the frustration lifted. Composure and progress were old friends I welcomed back into my life.

TBI changes us in ways we can’t describe. It takes the whole of us and cracks us open, scattering memories and personalities until we lose our sense of character. Hope, patience, positivity, normalcy, clarity; these are pennies at the bottom of a wishing well for those suffering after TBI. We all walk different roads, depending on the severity of injury, but eventually, we pick up the change a penny at a time, and start moving forward again.

Even as I move forward with my new life, I continue to worry over old decisions to compete. I put myself in a world of danger traveling at highway speeds down mountains with an injured brain. While I’ve mostly recovered, I’ll never recover from the fear of almost killing myself to accomplish my dream. No sport is worth repeat TBI for the gain of glory. That’s something I’ll never stop teaching athletes.

Today, I am a coach, and work with athletes pursuing their dreams on a daily basis. I know how many important lessons are learned in the athletic team environment, pushing to become better at something. But repetitive TBI in the sporting world is not acceptable. The mind is a beautiful thing you’ll want to keep intact for the length of your life. It is precious and one-of-a-kind. Don’t shatter it in pursuit of short-term glory.

Written by Lesley LeMasurier, exclusively for BrainLine.

About Lesley:

Lesley LeMasurier holds a B.A. in English from the University of Colorado at Boulder. She is currently the assistant director of admissions and U16 alpine ski coach at a small ski academy in Northern California. Lesley, her family, friends, and instructors helped found a junior race program at Wintergreen Resort in Virginia in the mid-90s. She went on to attend Burke Mountain Academy, where she was a Junior Regional Champion, Vermont State Champion, and US Development Team Member in alpine ski racing before TBI ended her career at age 19.

Comments (3)

Please remember, we are not able to give medical or legal advice. If you have medical concerns, please consult your doctor. All posted comments are the views and opinions of the poster only.

Anonymous replied on Permalink

Anonymous replied on Permalink

Anonymous replied on Permalink