Janet Burroway reflects on her soldier son’s life — from his fascination with the toys of war as a child to his suicide at age 40.

“In every story I tell, there is a point where I can see no further.”

— Ann Carson, “On Homo Sapiens”

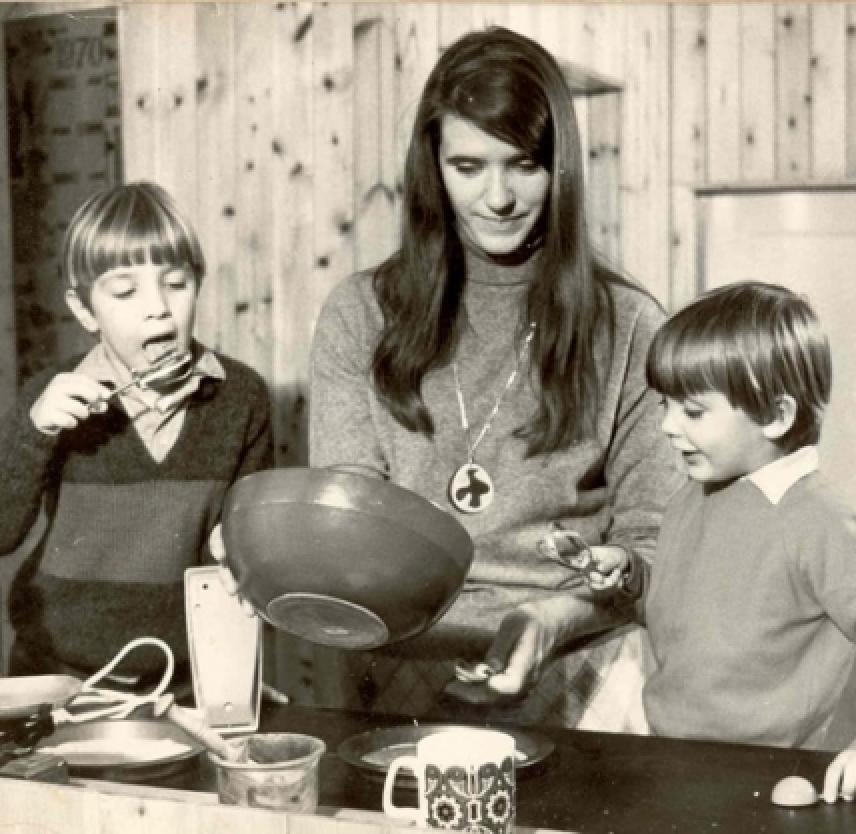

Like most little boys, Tim Eysselinck loved the toys of war. He’d spend hours putting together model airplanes, chasing his little brother with tin cowboy gun in hand, and reading books about uniforms, strategy, brotherhood, and honor. “I thought he’d grow out of it. Most boys do,” says his mother, Janet Burroway, who recently wrote a memoir called Losing Tim.

But Tim didn’t grow out of it; his interest was never frivolous. In his teens, he started talking about the injustices in the world and the power and integrity of the “warrior spirit.” At 17, he was almost in tears because he was too young to fight in the Falklands to “defend British honor.” And over his adolescent years, he became a passionate defender of the Second Amendment. “It agitated me that my son was a NRA-supporting young Republican. I mean, his father and I had taken him in his stroller to protest Vietnam. It was all so alien to me and I did not want a gun-loving son.”

Agree to disagree

It took many years, even after Tim joined the Army, and a number of uncomfortable conversations about politics before mother and son could agree to disagree. “We decided we had to love each other despite our opposite world views,” she says. “And we were proud of ourselves that we were able to accomplish that.” In fact, Janet once found an essay of Tim’s in which he’d written “My mom has let me find my own way.” He added that had he been the parent and she the child, things would have been different. “I wouldn’t have let you be you, but you’ve let me be me,” he wrote.

Tim followed his dream and became a US Army captain. He spent nearly 16 years in the military before leaving to continue his humanitarian work removing land mines after that precise and precarious job was privatized. It wasn’t until 2003 when he opted to go to Iraq that he felt as if he was going to fight in a “real war.” Since he was a private contractor by that time, he could choose the length of his commitment and he promised his wife he would serve only seven months in Iraq as a de-mining specialist and then they would move from Namibia, where they lived, to Washington, DC.

As a child, he had vehemently insisted that whatever his mother or anyone else thought about war and the warrior spirit, those committed were not flighty or superficial nor were they interested in the money, rather being of the warrior spirit required an extreme integrity. But when he returned from Iraq in February 2004, Tim was a changed man. “He was enraged and bitterly disillusioned,” says Janet. “He couldn’t get over the unbridled corporate corruption, the incompetence, and the indifference to human life including his and those of his men. According to him, the whole thing was corrupt.”

Although Janet had never understood her son’s politics, she said it broke her heart to see him go from the serious and stalwart teenager who repeated “my country right or wrong” to the diminished adult saying “I am ashamed of being an American.”

April 23, 2004

On April 23, 2004, two months after returning home to his wife, 10-year-old stepson, and 31/2-year-old daughter, Tim took his own life. Awash in intense emotions after having had a hard time getting his little girl to settle down for a nap and a fight over what his stepson was allowed or not allowed to do with his friends, Tim shot himself in the head in front of his wife.

“It was a bitterly ugly thing to do,” says Janet. “I was so angry at him for subjecting his wife to that trauma and leaving a tiny girl behind with no father, so angry … until I learned more about PTSD and TBI.”

And even now, a decade after that dreadful day, Janet wonders if what Tim said to his wife before pulling the trigger — “You’d better get me some help!” — was an accusation or a plea. Whatever it was, she says, it was a terrible, terrible choice for Tim and for everyone who loved him.

We don’t know what we don’t know

After Tim’s death, the family started putting some clues together that might explain his suicide. When he was home for those two months, there were little signs that when pulled together revealed erratic behavior that had not been there before. He cancelled a trip to England to visit his mother and her husband, which had been long-ago planned. He also told his wife that the deal to move to DC was off. He was hypervigilant about his family’s safety, in particular the comings and goings of his stepson. And one day, while on a 10’ ladder, a neighbor looked up and asked him if he was okay, if he was afraid of heights. Tim, who had been a paratrooper who inherently reveled in risky behavior, was near the top of the ladder, shaking like a flag in the wind. These were only a handful of the signs revealing a man transformed from loyal, loving, and responsible to angry, distracted, and impetuous.

Tim had never been formally diagnosed with TBI or PTSD. “Contractors, it seems, are treated the way the Vietnam vets were treated when they returned from war – with contempt and disdain,” says Janet. “He did the same job he had been trained to do in the Army and the Army made the decision to privatize his job, not him. He was disappointed by the Army’s decision but, until his last months in Iraq, he continued on as a straight-up patriot.”

And unlike service members in the Army, there is no de-briefing for contractors — or for their families — when they return stateside. “We didn’t know what to look for,” says his mother. “We didn’t know what we didn’t know, especially Tim’s wife who saw the father of her child, the man she loved, act more and more like a pugnacious and deeply unhappy stranger. She noticed that he was down, that he was not sleeping, that he did things like drive far too fast with the family in the car, something he’d never have done before, but she just chalked all that up to his getting the war out of his system.

To try to understand what had happened to Tim and how he had chosen to end his life in such a violent fashion, his wife went to a psychiatrist who said that Tim’s behavior sounded like a classic case of PTSD. She also talked to others who believed as she did that Tim’s ongoing proximity to blasts when de-mining bombs most likely caused some significant degree of traumatic brain injury. She tried to sue the government, but she lost the case. It is nearly impossible to prove PTSD and/or TBI posthumously.

Retrospect, the operative word

When looking back at her son, Janet says she now sees that Tim had a tendency toward depression. It rose to the surface most prominently when he had a desk job, when he felt trapped, tamped down. “He was a risk taker from early on,” she says. He lived to jump out of airplanes, to head out on assignment, to help other people out in the world.

“Maybe he was always bipolar and the Army got the ‘up’ side, while being in an office or without an adventure ahead yanked him down,” she adds. “Retrospect is definitely the operative word here.”

Being the writer that she is, Janet sometimes sees the past in a sort of collage of images, images and words and emotions that flutter around each other then drift down, falling into patterns and conclusions. There’s Tim, the toddler walking through a field of daffodils with his little brother, Alex. There’s Tim, the gun enthusiast and adventurer, the “white hunter” kneeling beside the carcass of an antelope who was teased by his guides in Cameroon for refusing to poach on government land. And, among countless other memories and pictures that continue to stream behind her eyes, there’s Tim as a gentle father, bearded and grinning beside his little daughter.

Sometimes mourning the loss of a loved one is trying to understand what you can’t understand and, finally, accepting the heart-breaking fact that sometimes there is simply no understanding.

Mourning a suicide

“Suicide is the only form of death that leaves you obsessively asking why, why, why … what was in his mind?” says Janet. “You want to know what led to that decision, that action, that split second.

“You come to a point when you say to yourself that you know all there is to know. You have questioned and dug and dug again and examined everything, including your part in it, until there is no more. You understand it as best you can … but that said, it doesn’t mean you don’t totally stop wondering.”

Janet says she does not believe in closure. “To me, closure seems to suggest that you are over the pain, over the memories. How could you ever be?” She adds, however, that she sees the paradox in feeling comfortable with her brother saying that everyone’s life is complete, while still feeling that Tim is with her. “I don’t think of Tim in the past tense. I love my son, not I loved my son. He’s still with me. I am still his mother,” she says.

I am free of the facts

Having sold their flat in England and now sharing time between their home in Chicago and their country home in Lake Geneva, that has five acres and five bedrooms for Tim’s and Alex’s families to stay, Janet finds that she has found some acceptance in all that has happened. “Acceptance is important, and accepting Tim’s death has helped me look at my own mortality,” she says.

Currently, in addition to her fiction, Janet is working on two plays, having become involved in Chicago theatre. One of them is about losing her son who was a contractor in the war. It’s called “Headshots.”

Sometimes Janet sees something or hears an interesting story and thinks, “Tim would have loved seeing that … he should be here.” But life continues to open and, as she writes in her book, she thinks about a girl in Namibia who used to play along the power lines who didn’t die because somebody had pushed the mines into the berms and blown them up. There’s the hotel clerk, the pregnant rug maker, the mothers and fathers, brothers and sisters, and aunts and grandfathers who didn’t die because a man named Tim Eysselinck believed in the importance of helping others.

“It’s odd,” says Janet, “but having written the memoir about Tim, I have come as close to the truth as a I can, and now I am free of the facts.”

Comments (1)

Please remember, we are not able to give medical or legal advice. If you have medical concerns, please consult your doctor. All posted comments are the views and opinions of the poster only.

Anonymous replied on Permalink