If you’re here at the Treatment Hub, you’ve probably been struggling with TBI or PTSD for a long time. You may have tried lots of different treatments already. And you’ve probably been told to eat right, exercise, and get plenty of sleep already.

If it were easy to do those things, we’d all be doing them all the time. We know that with PTSD or brain injury, sometimes you simply can't sleep or exercise as much as you would like.

Experts tell us that for some people, the basics of a good diet, exercise, and sleep may do as much or more to improve your symptoms as other treatments.

So, if you are able … we’ll try to convince you to give self-care another shot.

Physical Self-Care

A healthy lifestyle is good for everyone, but it’s especially important if you have a brain injury or PTSD. You may be struggling already with headaches, memory problems, trouble sleeping, chronic fatigue, or the side effects of medication — and all of that can make self-care harder. But since brain and body health are so closely connected, tending to these lifestyle basics can be a big step toward feeling better — and can make every kind of treatment more effective.

Eating Well

What you eat has a direct effect on your body and your brain.

Writer Michael Pollan captured what he learned about food and health in just seven words: “Eat food, not too much, mostly plants.” By “food,” Pollan means things that your great-grandmother would recognize as food: fruit, vegetables, whole grains, and (for non-vegetarians) fish and meat.

While some foods can help to promote brain health, there’s no one diet that is beneficial for everyone with a brain injury.

Mary Ann Keatley and Laura L. Whittemore of the Brain Injury Hope Foundation recommend that, as a general guideline, people with brain injury should consider eating small meals every three to four hours and setting reminders if you’re having trouble sticking with a regular meal schedule. Those small meals should include primarily foods found in the Mediterranean diet, such as:

- Fish, lean meats, nuts, and eggs

- Healthy fats and oils from avocados, seeds, and nuts

- Healthy carbohydrates found in vegetables, fresh fruits, and grains

There is some evidence that fatty fish can promote brain health since they are a good source of omega-3 fatty acids (Pu et al., 2017). Other sources of omega-3s include:

- Flaxseeds

- Chia seeds

- Walnuts

- Soy beans or kidney beans

Vitamin B12 is another nutrient that can help people who are recovering from a TBI (Wu et al., 2019). Vitamin B12 can be found in the following foods:

- Tuna

- Salmon

- Beef

- Fortified cereals

- Milk and dairy products

Harvard Medical School’s Health Blog suggests cutting down consumption of processed and high-sugar foods as well as alcohol. Cutting back on sugar and processed food can play a big role in improving your diet and your overall health. This article from Healthline suggests 14 simple ways to stop eating lots of sugar.

It is not uncommon to use eating as a means of coping with depressed, anxious, or stressed feelings. Often the food choices made during stress eating are foods high in fat, sugar, and/or salt like chips, chocolate, or ice cream. Stress eating can then lead to undesirable weight gain or development of new health problems like high cholesterol, high blood pressure, or diabetes. If you can start to recognize when you feel those cravings, take a moment to notice what you are feeling, drink some water, and try another strategy (yoga, journaling, exercise, meditation) to deal with those stressed feelings.

Drinking alcohol is another negative coping mechanism. Beyond the health concerns associated with excessive drinking, there is also the concern regarding alcohol being contraindicated with many medications that are commonly prescribed to individuals with PTSD and/or TBI. Specifically, drinking with certain antidepressant medications can increase the risk of seizures; drinking while on seizure medications can be dangerous; and combining alcohol with certain pain medications can be deadly … not to mention that excessive drinking may lead to forgetting to take your medications, which can also be dangerous.

Drinking Water

Water is essential to life. You know this. It lubricates your body and your brain. It keeps all your organs running and cleans out your system.

You may have already heard to drink eight 8-oz glasses of water a day, or approximately 2 liters. The truth is, you probably need more. It all depends on you: your body type, your physical activity levels, your medications, your diet. The new recommendation is to drink one half to one ounce for every pound you weigh a day. So take your weight and divide it in half to get your total ounces. If you weigh 200 pounds you would need 100 ounces a day.

Without enough water you can get dehydrated. Dehydration can cause symptoms that mimic brain injury and PTSD symptoms like headaches, dizziness, lightheadedness, fatigue, and irritability.

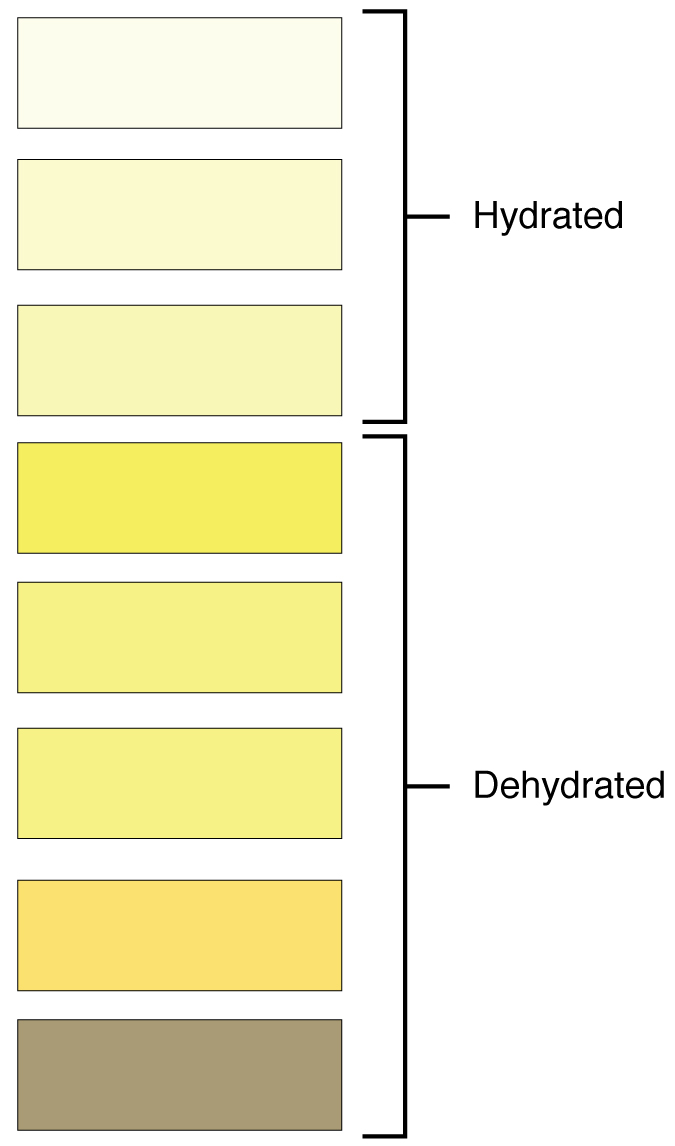

One way to tell if you are drinking enough is to check the color of your urine. It should be clear to light straw in color. Anything darker may mean you are dehydrated.

Note: Some medications may affect the color of your urine. Please check with your doctor if you have concerns.

Did you also know that your water intake can come from foods? Cucumber, celery, watermelon, peaches, skim milk, broth and more all have high water content. That all counts towards your daily recommended intake.

Here are ways to stay hydrated all day:

- Drink some water when you first wake up.

- Drink some water whenever you feel thirsty.

- Take sips of water throughout the day. Keep a water bottle or thermos with you to help you track how much water you have had.

- Drink some water when you feel hungry. Sometimes hunger can indicate you need water.

- Drink some water when you exercise, 8 ounces every 15 minutes of activity.

- Drink some water whenever you eat. Water aids in digestion.

- Eat foods with high water content. 19 Water-Rich Foods That Help You Stay Hydrated

- Limit your caffeine intake (coffee, tea, soda, etc.), especially right before bed.

Hydration helps your brain, body, skin, hair, digestion, mood, and overall wellness. When in doubt, drink some water.

Exercise

Exercise can help almost everyone, but any exercise program should be developed based on your own fitness level and capacity. Exercise can be adapted to accommodate brain injury and physical injury alike. If a brain injury or other factors are limiting your ability to exercise, consult with a medical professional (such as a doctor, nurse, or physical therapist) to find a program that’s safe and that’s right for you.

When it comes to exercise, the most important takeaway is that any amount of physical activity has some health benefits. The first key step — if you are able — is to move more and sit less. Being active has major health benefits. It can reduce anxiety and blood pressure, improve the quality of your sleep, boost immune system functioning, help you maintain a healthy weight, and reduce the risk of cancer, dementia, heart disease, stroke, diabetes, depression, and other ailments. Source: Top 10 Things to Know About the Second Edition of the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans | health.gov

Everyone has a different starting point, and small steps can make a big difference. You don’t need to run a marathon. Going out for a daily walk, for example, can deliver major benefits for your physical health, your cognitive ability, and your outlook on life.

If you’re able to do more, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services recommends these exercise guidelines for the general population:

Aerobic activity. Get at least 150 minutes of moderate aerobic activity or 75 minutes of vigorous aerobic activity a week, or a combination of moderate and vigorous activity. Moderate aerobic exercise includes activities such as brisk walking and swimming. The guidelines suggest that you spread out this exercise during the course of a week. Even small amounts of physical activity are helpful. Most people do better if they start at a slow, steady pace. Moderate aerobic exercise has also been shown to help recovery from a TBI.

Vigorous aerobic exercise includes activities such as running and strenuous cycling. At least one study has shown that a regular program of vigorous aerobic exercise (three 30-minute sessions per week) can also improve cognitive functions in people with mild or moderate TBI.

Not everyone will be able to engage in vigorous exercise due to physical injuries, chronic fatigue and/or secondary medical conditions. Consistent exercise on a regular basis, even consistent light exercise like going for a daily walk, can have a positive impact on both health, cognition, and mood.

Any exercise routine can be modified depending on your current fitness level and any injuries you may have. The key is to start small and then keep to a reasonably consistent routine. If you have access to a physical therapist, an occupational therapist, or a doctor, they can often be helpful in customizing a home exercise program to meet your specific needs.

Strength training is also very helpful. If possible, try to do strength training exercises for all major muscle groups at least twice a week. Aim to do a single set of each exercise, using a weight or resistance level heavy enough to tire your muscles after about 12 to 15 repetitions.

Strength training can include use of weight machines, your own body weight, or resistance paddles in the water.

Yoga has been shown to help people with brain injury to develop and hone their balance, flexibility, and muscle strength following an accident. Yoga can also promote a healthy mind-body connection for people with TBI. Yoga is also very helpful in dealing with stress.

One great resource for people with TBI is “Love Your Brain,” which was started by professional snowboarder Kevin Pearce and his brother Adam after Kevin sustained a TBI."Love Your Brain” was created by survivors for survivors and places a heavy emphasis on yoga, mindfulness, and meditation to support recovery.

Sleep

Problems with sleep are three times more common in people with TBI than in the general population. Nearly 60% of people with TBI experience long-term difficulties with sleep.

Sleep problems can often be resolved by changing some of your daily routines.

Good “sleep hygiene” includes:

- Make your bedroom a comfortable place to rest. Try not to work or watch TV there, especially in the hour or two before you try to go to sleep.

- Make your sleep environment as quiet as possible. Play soothing music or turn on a fan at night if those things help you to sleep.

- Sleep in a dark room that is not too hot or too cold.

- Go to bed at the same time every night, even on weekends.

- Wake up and get up at the same time every morning.

- Getting exercise during the day can help improve sleep at night.

- Avoid coffee and other caffeinated beverages (such as tea with caffeine or soda) in the afternoon or evening.

- Don’t eat, drink any beverages, or smoke for at least 2 hours before going to bed.

- Don’t exercise strenuously in the evening.

- Go to the bathroom before you go to bed.

- Establish a relaxed, calming bedtime routine. Consider practicing meditation or other relaxation strategies as you’re winding down and getting ready to sleep.

- Spend non-sleep time out of bed and out of your bedroom.

- If you’re tired during the day, try going for a walk or doing some gentle exercise instead of taking a nap.

- Don’t sleep or nap for more than 20 minutes during the day.

- Try to avoid “screen time” for at least 30 minutes before going to sleep.

These self-help methods enable many people to sleep better, but there are also many sleep problems that require more intervention. Sleep problems can result from many causes: chronic pain, headaches, arthritis, depression, anxiety, sleep apnea, asthma, restless leg syndrome, the side effects of medication, and others. Sleep apnea is just one example of a sleep problem that is very common after TBI, that is usually treatable, but that often goes undiagnosed (Hidden Health Crisis Costing America Billions, 2016). There are a wide range of treatments for sleep problems, depending on the underlying cause. If your sleep problems persist, it’s worth taking the time to see a doctor to help identify the cause and to find a treatment that will work for you.

Even in the absence of sleep disturbance, the majority of individuals with TBI (as many as 70%) report problems with fatigue. The Model System Knowledge Translation Center has tips to help you manage the effects of TBI fatigue.

"The most important thing to remember is that poor sleep really makes everything worse,” says Dr. Danielle Sandsmark of the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. “So getting on top of it early is important (Kraft, 2018).”

Optimizing Brain Health

If you are suffering from the effects of TBI, PTSD, or possible Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE), it’s important to know you are still in control of your brain health. By adopting the basic strategies listed on this page, you can take action that will help you feel better today, and lower your risk of long-term cognitive problems in the future.

Learn from Dr. Rebecca Van Horn, a psychiatrist, and U.S. Army Reservist, six of the most important keys to optimizing brain health in this video:

BrainLine is proud to be a program partner of the Concussion Legacy Foundation’s Project Enlist. Learn more about how we’re advancing research on military veterans with TBI, PTSD and CTE at ProjectEnlist.org. Learn more from Dr. Van Horn and other brain health experts on the Project Enlist Operation Brain Health page.

Mental Health Self-Care

Your mental health is just as important as your physical health. Mental health self-care can be as simple as journaling, spending time outside, attending a religious service, or calling a loved one. You can also attend counseling if you need additional support.

Do things you enjoy that fuel your mind, that keep you mentally stimulated and healthy. Read a book, practice your hobby, do a puzzle, make art, learn about your favorite subject, watch inspirational movies, listen to your favorite music ... whatever engages your mind. Practicing self-acceptance and self-compassion are also important parts of mental self-care. This can be even more difficult with brain injury and/or PTSD.

Emotional Self-Care

Emotional self-care is perhaps most important with brain injury or PTSD. Healthy coping skills take practice, particularly when emotional regulation is affected by brain injury. Recognize your triggers. Acknowledge and express your feelings on a regular basis. Some healthy ways to process your emotions are talking to a friend or loved one, journaling, creating art, taking prescribed mood-stabilizing medications, or going to therapy.

A growing body of research shows that relaxation strategies like meditation, mindfulness, and yoga can reduce stress and anxiety, leading to improved physical health, mental health, and cognitive outcomes. The LoveYourBrain website includes research and exercises.

Emotions can often be difficult to regulate after brain injury or PTSD. If you start to feel like you are losing control, acknowledge your feelings, recognize how your body responds, take a deep breath, and do something that safely allows you to release the negative emotions like screaming into a pillow. Therapy can also help you manage your emotions by teaching you to acknowledge, address, and express your feelings in a healthy way.

Spiritual Self-Care

Growing research shows that spirituality or religion as a part of your lifestyle improves your wellbeing. Spiritual self-care does not necessarily mean practicing religion. Spirituality can include anything that connects you to the universe or deepens your sense of meaning.

Attend a religious service, say a prayer, meditate, express gratitude, read something inspirational, or practice random acts of kindness. All these activities can contribute to your spiritual well being.

Rest and self-care are so important. When you take time to replenish your spirit, it allows you to serve others from the overflow. You cannot serve from an empty vessel.

Making Time for Self-Care

There is no right way to practice self-care. Everyone has different needs and those needs can change over time. Time is the most essential part and potentially the most difficult. With busy schedules, competing priorities, and added injuries, it can feel like there is no room for self-care. Start with small steps. Make the time to destress and care for yourself in whatever ways work best for you. You are worth it.

References

Chin, L. M., Keyser, R. E., Dsurney, J., & Chan, L. (2015). Improved Cognitive Performance Following Aerobic Exercise Training in People with Traumatic Brain Injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 96(4), 754–759.

Driver, S., Juengst, S., Reynolds, M., McShan, E., Kew, C. L., Vega, M., Bell, K., & Dubiel, R. (2019). Healthy lifestyle after traumatic brain injury: a brief narrative. Brain Injury, 33(10), 1299–1307.

Hidden Health Crisis Costing America Billions. (2016). Frost & Sullivan.

Kraft, A. (2018, March 23). The Link Between Concussions and Sleep Problems. EverydayHealth.Com.

Popkin, B. M., D’Anci, K. E., & Rosenberg, I. H. (2010). Water, hydration, and health. Nutrition Reviews, 68(8), 439–458.

Pu, H., Jiang, X., Wei, Z., Hong, D., Hassan, S., Zhang, W., Liu, J., Meng, H., Shi, Y., Chen, L., & Chen, J. (2017). Repetitive and Prolonged Omega-3 Fatty Acid Treatment after Traumatic Brain Injury Enhances Long-Term Tissue Restoration and Cognitive Recovery. Cell Transplantation, 26(4), 555–569.

Selva, J. B. (2021, February 24). How to Set Healthy Boundaries: 10 Examples + PDF Worksheets. PositivePsychology.Com.

Shannon, P. J., Simmelink-McCleary, J., Im, H., Becher, E., & Crook-Lyon, R. E. (2014). Developing Self-Care Practices in a Trauma Treatment Course. Journal of Social Work Education, 50(3), 440–453.

Sleep and Brain Injury. (2017, May 27). BrainLine.

Sleep and Traumatic Brain Injury. (2021). Model Systems Knowledge Translation Center (MSKTC).

Valtin, H. (2002). “Drink at least eight glasses of water a day.” Really? Is there scientific evidence for “8 × 8”? American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 283(5), R993–R1004.

Wu, F., Xu, K., Liu, L., Zhang, K., Xia, L., Zhang, M., Teng, C., Tong, H., He, Y., Xue, Y., Zhang, H., Chen, D., & Hu, A. (2019). Vitamin B12 Enhances Nerve Repair and Improves Functional Recovery After Traumatic Brain Injury by Inhibiting ER Stress-Induced Neuron Injury. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 10, 406.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only. Please speak with a medical professional before seeking treatment.

Reviewed by Amy Shapiro-Rosenbaum, PhD, Lyndsay Tkach, MA, CBIS, and Michelle Neary, March 2021.

The BrainLine Treatment Hub was created in consultation with TBI and PTSD experts.

Social Self-Care

Humans are social creatures. Staying connected to your friends is important to your overall well-being. Make a phone call, send an email, write a letter, have a small get-together. Even a simple text lets them know you are thinking about them. Relationships work best when they are cared for and maintained. Brain injury and/or PTSD can sometimes make social connection and communication difficult, so social skills training may be helpful.

Healthy boundaries are also an important component of social self-care. Boundaries can be physical, psychological, or emotional. Boundaries help you establish your identity. If boundaries are not kept, both in personal and professional settings, they can lead to resentment and anger. They can become difficult to navigate when dealing with brain injury and/or PTSD. They also take practice. Let go of guilt and keep trying. Boundaries actually strengthen relationships because you are happier and healthier when your needs are met.

Everyone has different social needs so you will have to find the right balance and level of social engagement that works best for you.