“Sign Me Up!"

Angie loved being a soldier. The kid in her — the kid who was always outside with dirty, scraped up knees, seeking new quests, a half grin on her face … the high-achieving kid who switched schools a lot because she got bored and wanted different challenges … the kid who found her way into countless leadership roles just because they were fun — welcomed the adventure the military proffered. “I always loved traveling, seeing new places, making new friends. And I was a go-getter, someone who said yes to anything no matter how daunting at first,” she says. “And I loved the people in my units. We were like a close-knit family. We still are.”

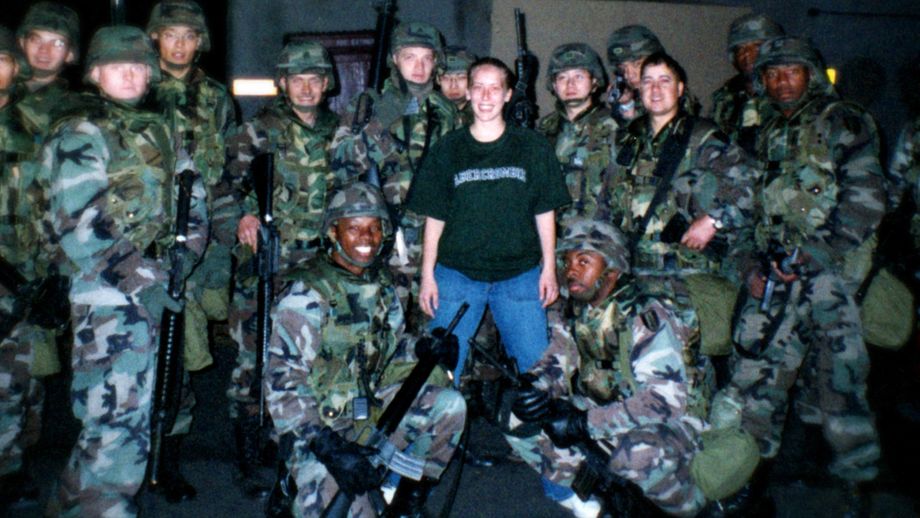

Super soldier Angie stands with her unit, December 2000, Camp Carroll, South Korea

She worked as a “31 Romeo” — a multichannel transmission systems operator maintainer; basically, the phone company for the Army that installs and fixes antennas, radios, and other heavy equipment essential for communication. She had found her groove.

“You Told Me ‘No,’ But I Did It Anyway”

The military can take you to new places full of new people, new cultures, colors, and textures. Some safe, some less so. In 2001, while serving in Korea, Angie was raped by a non-commissioned officer. She reported it but was told she would be dragged through the mud, her choices put under a microscope, and if anyone were punished it might be her. She let it go. But she and some friends did confront the non-commissioned officer who looked her right in the eye and said, “I know. You told me, ‘no,’ but I did it anyway.” Soon thereafter, Angie reenlisted for Germany and went to school to become a sergeant. “I threw myself into my work and took it as a lesson as to when and how to trust people,” she says. “I pushed it all down, but you can only suppress your feelings for so long.”

Heat and Sand

In May 2003 — early on in the Iraq war, a month and a half after the Saddam International Airport in Baghdad was taken by American forces — Angie and her unit arrived in Baghdad after a 50-hour convoy from Kuwait with no sleep and a paucity of provisions. It was early on in the war and few structures had been established. They set up in a ditch, below the danger of bullets overhead. They slept inside an old museum; the temperature sometimes exceeding 130 degrees. There were no cell phones, no shower. They were issued two MREs and a one-liter bottle of water per day. They “washed” in a bucket and because there were few supplies, they wore the same uniform day and night, flipping their underwear inside out until they threw them out and opted to wear no underwear at all. They pooped in a hole. There were burn pits everywhere. They went on three convoys a week and pulled 12 hour shifts everyday (in addition to the convoys).

The supply lines improved and contractors arrived so the food and water situation got a little better. But the fear was constant. The hypervigilance never ceased. “There is a lot of fear, you know? Hearing stories about people dying, people throwing grenades from overpasses, having small arms fire hit close to your truck, RPGs whizzing all around,” Angie explains.

“Each time you leave on a convoy, you think, this could be it. You don’t talk. You just hold your breath and react to what comes. You push down that constant fear of death. I think this is what PTSD is. You train for this … this ‘fear learning.’ You learn to constantly scan for danger, scan for threats and it gets hardwired into your brain. Not sure how to unlearn that. I’m still working on it.”

And once back on base, post-convoy, cortisol levels dropped, at least temporarily. “There is complete exhaustion. You are hungry, thirsty, sweaty, filthy — everyone is solemn, stoic, silent.” They had evaded death once again.

Which Way Will I Die?

Within a month of being in Baghdad, Angie fell incredibly ill. “I’m exhausted, I’m passing out. I’m having nose bleeds, low-grade fevers, diarrhea constantly,” she says. “There’s one medic on base. He’s doing his best, but he basically tells me there’s nothing he can do with little medical equipment and no tests. He recommends I be medically evacuated out.” Her commander told her, “no,” she had to stay, she was mission essential. Angie lost 40 lbs.

Angie never gets a formal diagnosis. She still believes her illness resulted from a combination of the environmental hazards like the burning pits and the relentless trauma of combat.

“I try to push these thoughts out of my mind, but I keep thinking that I’m either going to die from whatever is eating me from the inside out, or I’m going to be shot,” she says.

In November 2003, a new commander medically evacuated her to Landstuhl, Germany. Despite wanting a career in the Army, this was the first step that ended her service.

The First Turning Point

At Landstuhl, Angie got x-rays, tests, and blood work as doctors tried to determine the cause of her illness. Her second day there, she learned her convoy back in Baghdad had been hit. She met one of her guys a few rooms down. “The kid has had surgery. He’s lying in his hospital bed with a phalanx of staples from the top of his chest to his belly button. He is messed up. He’s suffering and struggling; I can barely deal with looking at him or listening as his hysteria spirals. He thought he was going to die out there, alone,” says Angie.

“That was the moment. I couldn’t take it anymore; it was too much … this kid, in my unit, almost died when I wasn’t there and he’s staring at me with all these staples on his stomach. I told him I’d be back, and I bolted. I walked down the hall to the psychiatrist. If only I had known what would happen from there …"

What Does Help Mean?

Angie was supposed to redeploy to Germany but when she shared her feelings with the psychiatrist, everything backfired. “I told them I was having a hard time readjusting. Every time a door slams, I think it’s a gun shot. The ceiling feels like it’s falling on me. I mean, these were normal reactions to what I had experienced. But I was deemed a danger to myself and others. They said I needed to be medically retired out of service, but that is not what I wanted,” she says. “I fought it a bit, but by that time, I had been put on so many different medications and everything was heightening. ‘That’s your PTSD, you’re getting worse. This is for the best,’ they said. “And I was in so much pain, mentally and physically, I welcomed whatever might help.

“In hindsight, I feel like the military chewed me up and spat me out,” she says. “I was a super soldier, everyone counted on me, I was on track to be a staff sergeant. When I think about being medically retired, well, it’s embarrassing almost. I don’t feel like I got to have any say in my future.”

Angie became a full-time patient, diagnosed with PTSD as well as several anxiety disorders in addition to some physical issues. “I had three surgeries, back to back. I was handed opiates like candy for my post-surgical pain on top of the psychiatric meds, anxiety and sleep drugs, you name it,” she says. “When one dose of something no longer worked, they upped the amount or put me on something different. I was basically the opiate crisis before the opiate crisis. It took me two years to get off those alone.” Angie went to rehab four times.

“I was taking medications every single day, lots of them. I was seeing a therapist once a week, a psychiatrist once a month. I’d be waiting to pick up pills at Walgreen’s or reading magazines in the therapist’s waiting room. You become a patient, not much else. That’s your role. That does something to you. It reinforces that there’s something wrong with you, that you don’t work properly. Any hope or sense of self disappears.”

For almost 13 years in her sick and patient role, Angie was prescribed more than 40 medications. She saw countless doctors and therapists, some more effective than others. She and her husband divorced.

The Second Turning Point

Somehow, Angie became curious. Despite feeling invisible, unheard, stuck, her voice, her former fighting spirit, struggled to the surface. Who am I under all these meds? What feelings do I actually have? Where is my strength?

Through the Wounded Warrior Project (WWP), Angie started to explore alternative therapies — exercise, yoga, acupuncture, meditation, equine therapy. She took cooking classes and connected with other veterans while taking CrossFit through WWP’s Physical Health and Wellness Program. Her world and her community began to expand.

“Equine therapy was a real turning point for me. It was the first time since being in the service that I met civilians who didn’t want to tell me there was something wrong with me,” she says. “I went from soldier to patient; I was finally trying to bridge that gap. I didn’t know this consciously, but I wanted to become part of a community. Isn’t that the point? I learned how to handle a horse and understand the way it moved and communicated. I learned to ride and how to wash and care for a horse.”

Angie started to trust others — and herself — again during equine therapy for PTSD.

For three years she went to the TREE House of Greater St. Louis where licensed physical, occupational, and speech-language therapists use equine-assisted therapy to help children and adults with disabilities. “Just being outside in the fresh air, in nature, with an animal that’s very accepting, who doesn’t care who you are or what your diagnoses are, along with these amazing therapists who help you rebuild trust in yourself and others, well, it was transformative. I found great comfort simply being with this huge animal, stroking it, smelling it, listening to it breathe.”

Equine therapy can help people find acceptance, tackle mental and physical challenges, and express their sprit in a peaceful and natural setting. By interacting with horses, people with PTSD often see their own emotional state mirrored in the reactions of the horse with which they are working. Horses — large and, at first,unfamiliar — also force people to step out of their comfort zones. They offer unconditional and uncomplicated love, something that people with PTSD often need to begin to heal from their experiences.

There Is No Free Lunch

Unfortunately, much of the progress Angie made through alternative therapies vanished as she started the long and painful journey to wean herself off her medications. She was told to taper from some medications, to go cold turkey off others. It took her almost three years to finally get off most of the medications, but the withdrawal almost killed her.

“The withdrawal syndrome is so severe, it’s hard to put into words. I couldn’t stand up in the shower. I couldn’t read. I had to hire people to cook for me, to walk my dog. I didn’t speak for four months. At certain points, I went into psychosis and suicidal thoughts entered my brain with such unexpected immediacy, I didn’t know if I’d make it. I was in and out of the hospital,” she explains.

Watch the trailer from Medicating Normal, an award-winning documentary that explores the conventional mental health care system’s reliance on psychiatric drugs to deal with trauma, grief, and distress. The film documents the journeys of five individuals profoundly impacted by the medications they were taking, including Angie.

“The first two years were the most harrowing. I felt like my brain was demolished, my nervous system damaged. I know that drugs can help a lot of people with physical and mental health issues, but maybe not forever. There’s real withdrawal from drugs. There’s no free lunch, you know.”

During this time, Angie somehow muscled through college and graduate school, earning a Masters in Social Work.

An RV is just an RV until it becomes a home and a means toward a journey of healing.

Nomad Life

Angie is in what she calls “year six” — the time from when she first started to wean off all her medications. She still engages in therapy, but on her own terms. She deals with PTSD, military sexual trauma, and visual problems that come and go. She is working to rebuild her strength, inside and out. She has good days and bad days.

But life is now on her terms. In December 2019, with her new degree, the documentary finished, and an expired lease, Angie bought an RV and she and Raider, her service dog, headed out with no real plans.

Living as a van-dwelling modern-day nomad, Angie never knows what to expect each morning when she wakes with the sun. One day she may happen upon a volcano in Mount Rainier National Park — “beauty, art, awe; there are no words.” Another day, someone may ask to buy her a coffee and after saying “no,” she says “yes.” — “I’m learning to say ‘yes’ to myself, to saying ‘yes’ to kindness, to learning that I am worthy and that I can live in the moment …”

“I knew I just had to go. I had not been living for 15 years. It was time to live and to learn who I am again, in nature, in my own way without other people’s voices drowning out my own.”

Angie is teaching herself to live holistically, to watch and use nature as an example. Being outside most of the day is a balmwalking, exploring, breathing, seeping in an endless feast for the senses. And along with enjoying the dramatic changes in landscape as she drives miles from one town to the next, one coast to the other, she is reveling in the people she meets. “I get to spend time with old friends and family, but I also meet and befriend people who are living this nomad life. It’s as if we get to know each other from the inside out, organically, in the moment. It’s powerful,” she says.

Her service dog, Raider, is her constant companion. He helps her get up in the morning. He gives her purpose, a responsibility beyond herself. “I can’t stay in bed. I have to take him out for a walk. It’s not an option.” Raider also helps instill in her a sense of well-being, safety, and independence. In large part because of him, Angie can interact more confidently in the world. “He’s with me all the time. It’s hard to explain but because I have been through so much — so much scary stuff and trauma — I can’t always regulate myself,” she says. “I might freak out or feel like I’m falling into a sinkhole of fear, and Raider can somehow pull me out of that quicker, or help me be less afraid, or help me grocery shop because I look at him and he’s fine and I can start to calm down.

Angie stands with a group from Wounded Warrior Project during the 2021 Veterans Day Parade, Florissant, MO.

“And he’s just happy all the time. People greet me more than they ever did before, which helps me talk to people and get out of my head. Because of him, I am less closed off, less quiet within myself. Raider epitomizes living in the present moment; I am trying to be more like him.”

Early on in her road trip, she stopped in cities to do screenings and panels for the Medicating Normal documentary, until COVID hit and those became virtual. Currently, her “day job” includes these screenings as well as serving as a spokesperson for WWP’s National Campaign Team. In late 2020, she started an online entrepreneurial boot camp to learn how better to share her story in a more intentional and maybe lucrative way through writing, speaking, and holistic health coaching. “It will be social work on a macro-level,” she says.

The Sights and Sounds of Healing

The last 25 months — zigzagging across the country with no plan but the urge for freedom — have been all about healing.

“Healing, for me, means a never-ending journey. I don’t look at healing as a destination anymore where I would return to my ‘old’ self, to the person I was before the war, before the medications. That’s not realistic; we grow and change every moment,” she says.

“My healing is present. There’s nothing wrong with me. If I tune in to what’s going on right now, all the answers are there before me — like the leaves and mountains, the lakes, the birdsong, the sound of Raider’s exuberant bark. It’s all up to me.”

Most days wind down around sunset. Angie feeds Raider and then cooks for herself, maybe noticing tentacles of oranges and pinks fingering through her curtains. She hears the night approach and takes a deep breath.