For the past 30 years, federal legislation has mandated that students with disabilities be provided an education in the least restrictive environment possible. This has resulted in a continuum of alternative placements that have included settings from general education classrooms to state institutions. The rationale for these placements has, in theory, been students' educational needs and the proximity of placements to general education peers (McDonnell, Hardman, & McDonnell, 2003). In spite of the increasing trend to place students in the least restrictive educational environment, the continuum of alternative education options is still legally available to students with disabilities (Yell, 1998).

One educational option that receives scant attention in the literature is homebound instruction. Homebound instruction can also be referred to as home teaching, home visits, and home or hospital instruction. Homebound instruction involves the delivery of educational services by school district personnel within a student's home. This differs from home schooling, which is usually delivered exclusively by a parent (Zirkel, 2003).

Homebound instruction was initially seen as an educational service option for students with impairments that made them physically incapable of attending school (Wilson, 1973). Such students could have been recuperating from a severe illness or may have been so physically fragile that they were unable to be transported to a school setting. Over the years, the option of homebound services has expanded to other populations. These populations may include students whose schools are on break, students who may be suspended or expelled, students who are awaiting a more appropriate setting, and students who are difficult to handle in traditional settings. Although state institutions are commonly considered the most restrictive educational setting, homebound services may be the most restrictive placement because students have no opportunity to interact with their peers (Council for Exceptional Children, 1997).

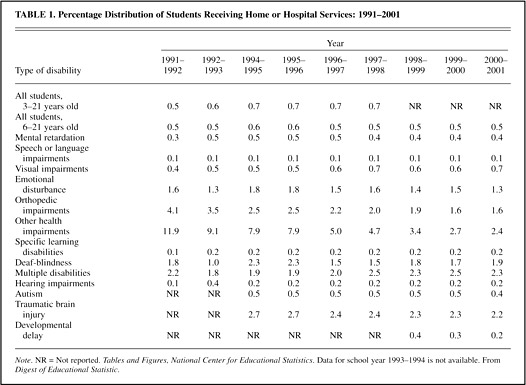

The federal government maintains annual data on the numbers of students receiving special education services and the specific types of services they receive. According to these data (see Table 1), from 1991 to 2001, less than 1% (National Center for Educational Statistics) of all students with disabilities received home or hospital-based instruction. Specific student disability populations that received home- or hospital-based services at rates greater than 1% included those with emotional disturbances, orthopedic impairments, other health impairments, deaf-blindness, multiple disabilities, and traumatic brain injury (National Center for Education Statistics, 2002a). In collecting data, the federal government (as well as many states) identifies home or hospital instruction as a single entity. Thus the data shown in Table 1 do not factor out the percentages of students who received home- or hospital-based services exclusively or in combination with other forms of instruction. In addition, the data represent the primary placements of students at the time that the surveys were conducted. Multiple student placements that could have occurred within a single school year are not indicated. Students with disabilities may be experiencing homebound instruction at much different rates than the federal government's data indicate.

Please click here for larger PDF version of Table 1.

Providing homebound services to any student can be a unique and positive experience for teachers. It affords the teacher an opportunity to observe the home environment and the family dynamics within that environment, resulting in greater understanding of the student's behavior. Because of the frequency of interaction and communication, it offers teachers the prospect of building stronger ties with the family. Homebound instruction may also result in greater bonds between teachers and students because of to the one-on-one instruction provided and the opportunity to truly individualize instruction (Baker, Squires, & Whiteley, 1999).

Homebound instruction can also present many challenges for teachers. Teachers are frequently not prepared to provide such services. Few teacher preparation programs address the issue, and much of the available literature on homebound instruction comes from the field of early childhood special education (Klass, 1996). In addition, school districts may not have specific guidelines for their teachers on providing homebound services (Daly-Rooney & Denny, 1991). Homebound instruction can present a variety of unexpected variables with which to contend. These can include disruptive siblings, a noisy environment in which to work, family conflicts, and cancellations of visits. Teachers may also be frustrated in recognizing that homebound services do not provide sufficient depth and intensity of instruction that some students may need.

Providing homebound instruction to students with emotional or behavioral disorders can be a particularly demanding experience. Such students can display a wide range of challenging behaviors, from apathy to defiance (Kerr & Nelson, 2002). Undesirable behaviors that are evident in school and community settings can be even more intense in the home. Teachers should plan on using their full repertoire of behavioral interventions, which could include identifying and avoiding the triggering of undesirable behaviors, the use of token economy systems, behavioral contracts, the calculated use of verbal praise, and working on tasks in small increments of time.

Although federal legislation indicates that a teacher or paraeducator may provide homebound instruction (National Center for Education Statistics, 2002b), there may be state or local public policies that mandate specific personnel who can provide such services. The homebound instructor, whether a certificated teacher, therapist, or paraeducator, should plan well for providing educational services to students identified as having an emotional or behavioral disorder.

Before the Visit

Before the initial visit, teachers of homebound students should conduct a thorough review of school documents related to the student and to the provision of homebound services. Teachers should become familiar with students' eligibility for special education services, behavioral or emotional histories, previous intervention strategies, and mandated services. Special attention should be given to Individual Educational Programs (IEPs) and to Behavior Intervention Plans. It is important that homebound instruction be provided in the manner specified in the IEP (e.g., frequency, duration, types of service, and types of personnel).

The teachers of homebound students might also consider interviewing previous and current service providers such as former teachers, school psychologists, and counselors. These individuals may be able to elaborate on information found in school records and may help the teacher identify details concerning the student's behavioral patterns, academic strengths, interests, limitations, and family dynamics. Such interviews may also provide information related to language and cultural differences, community characteristics, and hostility toward school personnel.

Teachers of homebound students should strive toward cultural competence. They should attempt to identify, understand, and acknowledge the beliefs, interpersonal styles, attitudes, and behaviors that are characteristics of the student's culture. Doing so will aid the teachers in building bridges between the home and school as well as between academic abstractions and students' actual experiences (Gay, 2000).

Communication is critical to the development of trust between school personnel and the family (Anderson & Matthews, 2001). If students, caregivers, or parents speak a language different from that of the teacher, the critical sharing of fears, expectations, and commitments cannot occur. Teachers of homebound students must make every effort to enhance communication. Teachers should identify the primary language used in the home and students' levels of language proficiency. If teachers are not proficient in the caregivers' and students' primary language, they should exlore alternatives, such as the use of a translator.

Locating the student's home before the initial visit is a recommended practice. Doing so will allow the teacher to scrutinize the neighborhood for possible safety issues and will help assure that the initial visit is made on time. If there are safety concerns, the homebound teacher, with an administrator, should outline strategies for dealing with them. Such strategies may include the assurance that homebound services are provided during daylight hours, the accompaniment of a partner during visits, and the provision of services at an alternative location (e.g., school district office, public library).

The teacher of homebound students and the administrator should identify circumstances in which a home visit is terminated. These situations could include family members' use of foul language directed at the teacher, threats of physical violence, intimidating behavior (e.g., excessive body proximity), inappropriate attire or lack thereof, the presence of illegal substances, or general household mayhem. In some instances, when a student is experiencing psychiatric difficulties, homebound services may unintentionally exacerbate the student's problems. In such instances, alternative educational plans should be developed along with representatives from mental health and social service agencies (British Columbia Department of Education, 1995).

Whenever homebound services are provided, a parent or legal guardian should be present. School staff should have current school picture identification with them to show to primary caregivers. Such identification could also be used to verify one's identity to law enforcement representatives should there be incidents within the home during a visit.

Teachers should contact the parent or legal guardian well in advance of the initial visit. Teachers should introduce themselves and review the parameters of the homebound service as specified in the IEP. The teacher and primary caregiver should determine a mutually acceptable time for the initial visit and future visits. It is also a good practice to communicate with the parent or guardian the day before the home visit to confirm the appointment. Teachers should indicate the need for a relatively quiet work area in which to conduct the visits. Teachers should also consider asking the parents or guardians their opinions regarding strategies for making homebound instruction successful.

Teachers should prepare a variety of activities for homebound instruction. If true instructional services are to be provided, the supervision of mere paper and pencil tasks is insufficient. Teachers can include direct instruction, oral reading activities, the use of games and technology (e.g., the use of a laptop computer), demonstrations with manipulatives and pictures, and investigative tasks. Having reviewed pertinent documents and having interviewed those with insights about the student will help the teacher select the most appropriate tasks. To transport materials, teachers may need to invest in a small suitcase on wheels.

Teachers should plan on a schedule of activities during the home visit and should attempt to provide some variety within that schedule to avoid monotony. Teachers should start the instructional period with the least threatening activity and then build up to more challenging tasks. They should also plan on ending the session with a positive and successful activity.

During the Visit

Teachers of homebound students must be prompt. Being late to a visit may elevate the anxiety of the student and family members. It may also be interpreted as being rude. At the initial home visit, the teacher should warmly greet the family members, review the structure of the visit with them (Baker et al., 1999), and summarize timelines and activities. If a reinforcement system will be used during the visit, the teacher should review it as well.

Because of fears of being judged and past relationships with school personnel, home visits can be intimidating to some parents and guardians. It is important that teachers of homebound students exhibit a friendly demeanor and demonstrate an interest in the student and the family. Although it is important to provide services as specified in the IEP, teachers of homebound students need to follow cues from caregivers and the student. If the student is ill or the caregiver is excessively agitated, it may be best to abbreviate a home visit with the caregiver's consent.

Throughout the instructional period, teachers should informally assess the student rather than conducting a formal assessment, particularly during an initial visit. Formal assessments are often intimidating and challenging. The initial use of such assessments may set a poor precedent that would be difficult to overcome. Teachers should note the student's academic level of performance during instruction sessions and collect work samples. They should also try to engage the student in discussions related to their areas of interest. These interests may be woven into future instruction resulting in a greater bond between the student and teacher and greater motivation in the student (Bakes, 1994).

The hours of instruction provided to homebound students usually do not match the instructional hours provided to students in traditional classroom settings. To make up for this discrepancy, homebound students are frequently given extensive homework assignments to complete in the teacher's absence. For students with behavioral and emotional problems, such homework can be a contentious issue. Students with behavioral and emotional disabilities may need ongoing supervision to complete academic work. Caregivers may not be able to provide the needed supervision or may not possess the management skills to successfully encourage their children to complete these assignments. For some students, homework can become an issue to manipulate or defy. Keeping these possible problems in mind, the teacher should attempt to provide relevant homework assignments that are at the student's level—assignments that can reasonably be completed within a given time period, and assignments that can be done with minimal assistance.

Teachers are encouraged to allow time at the end of each instructional period to communicate with the caregiver. Teachers can summarize the day's activities and note the student's accomplishments, review homework assignments, share suggestions for working with and managing the student, and verify future visits. This is an opportunity to socialize and attempt to bond with the caregiver. As with any educational service, the caregiver's support is crucial to the success of homebound instruction (Martin & Hagan- Burke, 2002).

After the Visit

After the home visit, teachers should identify those activities that were successful and those that need improvement, reflect upon the possible reasons for those successes and failures, and note the student's behavior during the visit, as well as the attitudes of family members. Not attending school can create a monotonous and demoralizing existence for the student, and living and coping with a behaviorally or emotionally disturbed child can be an exhausting experience for the parent or caregiver. Teachers should reflect upon changes in the emotional well-being of the family.

Aside from reflecting, teachers should document each home visit. In writing, teachers should indicate the date, the specific length and time of the home visit, and the name of the caregiver who was present. Teachers should identify the activities that were completed and the level of student success with each activity. A description of the student's behavior during the visit should be noted. Finally, details concerning homework assignments should be recorded. School districts or teachers can develop simple forms to prompt the provision of such information. Optimally, such documentation should be done in duplicates, with a copy given to the caregiver at the end of each home visit.

The old adage, "out of sight, out of mind," should not apply to students receiving homebound instruction. Teachers of homebound students should communicate with key stakeholders about their students; They should inform administrators about the home visits and any possible problems. They should consult school psychologists regarding the behavioral and emotional state of students and, if necessary, update social service agencies regarding the status of students, families, and current services. The written documentation completed after a home visit would help the teacher in communicating with such parties.

Conclusion

Homebound instruction should not be viewed as an insignificant interim educational service, nor should it be a service routinely offered to students with disabilities (British Columbia Department of Education, 1995). To be effective, homebound instruction needs to be well prescribed and should emphasize planning and communication (see Appendix). Optimally, homebound instruction should be offered through a multidisciplinary team effort. Key stakeholders (e.g., parents, teachers, administrators, therapists) would systematically bring together expertise from a variety of sources and professional fields to support, serve, and monitor the student. When such an organized team effort is not available, stakeholders need to resist working in isolation of one another. Whether working as a member of a team or not, teachers of homebound students need to plan, implement, document, evaluate, and attempt to communicate with others.

References

Anderson, J. A., & Matthews, B. (2001). We care for students with emotional and behavioral disabilities and their families. Teaching Exceptional Children, 33(5), 34–39.

Baker, C., Squires, J., & Whiteley, K. C. (1999). Home visiting: A Vermont approach to working with young children and their families. Waterbury: Vermont Agency of Human Services.

Bakes, C. (1994). Motivating students. The Technology Teacher, 54, 9–12.

British Columbia Department of Education. (1995). Special education services: A manual of policies, procedures and guidelines. Victoria, BC: Author.

Council for Exceptional Children. (IDEA '97—Full Regulation Discussion. (1997). Subpart E—Procedural safeguards least restrictive environment. Retrieved January 4, 2004, from http://www.cec.sped.org/law/...s/searchregs/300.551.php

Daly-Rooney, R., & Denny, G. (1991). Survey of homebound programs offered by public schools for chronically ill or disabled children in Arizona. Tucson: Arizona Center for Law in the Public Interest. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. EC300587)

Gay, G. (2000). Cultural responsive teaching. New York: Teachers' College Press.

Kerr, M. K., & Nelson, C. M. (2002). Strategies for addressing behavior problems in the classroom. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Klass, C. S. (1996). Home visiting: Promoting healthy parent and child development. Baltimore, MD: Brookes.

Martin, E. J., & Hagan-Burke, S. (2002). Establishing a home–school connection: Strengthening the partnership between families and schools. Preventing School Failure, 46(2), 62–65.

McDonnell, J., Hardman, M., & McDonnell, A. (2003). An introduction to persons with moderate and severe disabilities. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

National Center for Education Statistics. (2002a). Digest of Educational Statistics. Tables 52–54, 1995–2002. Retrieved November 6, 2004, from http://nces.edu.gov/programs/digest/ d01/dt053.asp

National Center for Education Statistics. (2002b). Supplemental notes. Note 10: Students with disabilities. Retrieved February 7, 2003, from http://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/2002/notes/ n10.asp

Wilson, M. I. (1973). Children with crippling and health disabilities. In L. Dunn (Ed.), Exceptional children in the schools, 2nd ed. (pp. 467–530). New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

Yell, M. (1998). The legal basis of inclusion. Educational Leadership, 56(2), 70–73.

Zirkel, P. (2003). Homeschoolers? Rights to special education. Principal, 82(4), 12–14.

Appendix

Do's and Don'ts for Providing Homebound Instruction

Do

- Research the student's educational history, strengths, needs, and interests.

- Provide homebound services according to the Individual Educational Program.

- Provide homebound services only when an adult caregiver is present.

- Communicate early and consistently with caregivers.

- Develop contingency plans for dealing with problematic visits.

- Prepare a variety of activities when working with the student.

- Have school identification.

- Document activities and progress.

Don't

- Approach homebound instruction with a cavalier attitude.

- Attempt to provide homebound instruction without planning.

- Assume that the student and caregiver will be available at a consistent time and day.

- Arrive late.

- Merely supervise the completion of paper–pencil tasks.

- Give excessive independent work assignments.

- Ignore the caregiver.

- Fail to communicate with other stakeholders about the homebound services.

From Preventing School Failure, Winter 2007. Heldref Publications. Www.heldref.org.

Comments (13)

Please remember, we are not able to give medical or legal advice. If you have medical concerns, please consult your doctor. All posted comments are the views and opinions of the poster only.

Deidre replied on Permalink

Are counselings required to go into the homes to provide counseling services, if it is part of the IEP.

Anonymous replied on Permalink

My daughter's Psych has prescribed Home Bound Schooling for her. She has disabilities that caused her to become very depressed, anxious and suicidal. Since he has done this her whole outlook on life has changed. She has even said she doesn't have to worry about the drama, being bullied and stress from High School. She is more focused on her work and her adhd is more controlled. I am just happy to see her smiling and back to herself!

Anonymous replied on Permalink

My daughter suffers major anxiety at school and has been a major problem she does fine at home. Would she be able to get homebound? Also all subjects?

Roberto Fernandez replied on Permalink

She would need to get a doctor to fill the form requesting the home-bound services to the school.

Teresa replied on Permalink

I am a homebound teacher. In our system a physicians statement is required to qualify for homebound services. Students problems are sometimes magnified when they are removed from social environments so I would suggest finding ways to cope and keep her in school. If you can't make it work, please know that by high school subjects are highly specialized and your homebound teacher will likely not be an expert in every subject. Students will need to work on academics between homebound visits.

Anonymous replied on Permalink

I have been a Homebound teacher for 13 years in Houston. Our district requires a responsible adult be in the home during all times of instruction. Parents cannot "step out" at any time or we are required to leave. However, our district does not provide support or counseling in the event a student dies as someone noted above. It's more like, "now you have room for another student" because we are understaffed and often rely on inexperienced subs to help out.

Anonymous replied on Permalink

School systems use homebound as a way to "get out of" their responsibility to serve the kids that need school the most. Every kid should go to school, unless a physician says otherwise!

Anonymous replied on Permalink

not true serious hings happen that u wont understand

Anonymous replied on Permalink

I found this information to be very informative. I have an emotionally disabilited son who also have a dystonia disorder which makes him homebound, and I am greatful to know that he can still get the education he needs outside of the traditional school system.

Anonymous replied on Permalink

Can homebound services be provided without a parent or caregiver present? Can this be done and/or what happens if the caregiver leaves once you arrive to provide services?

Anonymous replied on Permalink

Some of the students I work with are very fragile and in fact I have been faced with the death of two of my students. Dealing with grief is also an issue for many homebound teachers, especially those that deal with such fragile children. My supervisor has invited professional helpers to come and share insights on dealing with personal grief and the grief of family members. New teachers should be made aware of the possibility that they might lose a child.

Anonymous replied on Permalink

As a sped teacher who provides educational services to students with homebound placements, I totally agree with the need to build personal relationships with the caregivers as well as the students. Support from caregivers will make or break a homebound educational program.

Anonymous replied on Permalink

This was very helpful! Thank you.