It is midmorning in Richmond, Virginia, and I'm talking on the phone with retired Sgt. Edward "Ted" Wade about the dignitaries he met in Washington, DC during his last visit there and about his upcoming ski trip to Colorado. He is particularly excited about the ski trip. When I ask him if he would allow me to use his name in an article, he agrees without hesitation, adding that he hopes it will help others like him. His wife Sarah chimes in: "I bet that you wouldn't have guessed a year and a half ago that you would have a conversation like this with Ted." She was right -- I never would have guessed.

Sgt. Wade is one of more than 250 combat veterans who have been treated at the Veterans Administration (VA) Polytrauma Rehabilitation Centers (PRCs) since the beginning of the War in Iraq and Afghanistan. The VA designated four facilities-in Richmond, VA; Tampa, FL; Minneapolis, MN; and Palo Alto, CA-to provide specialized rehabilitation for severely injured service members. These centers are developing a new model of advanced rehabilitation care with their dedicated interdisciplinary teams of specialists, intensive case management, support for families, and involvement of voluntary and service organizations to help meet patient and family needs for services and assistance. While medical care on the battlefield and at military treatment facilities has kept these soldiers alive, it is now the VA's role to "make them whole again," in the words of Jonathan Perlin, undersecretary of health for the Department of Veterans Affairs.

About two-thirds of the combat veterans treated at the PRCs have suffered blasts from improvised explosive devices. The term polytrauma-a new word in the medical lexicon-is now being used to describe the injuries to multiple body parts and organs that occur as a result of exposure to blasts. The most frequent type of injury in the polytrauma cluster seen at the PRCs is traumatic brain injury (TBI). It occurs in almost 90% of the cases in combination with one or more of the following: vision and hearing loss, nerve damage, multiple bone fractures, unhealed wounds, amputations, and psychological and psychiatric problems.

The challenge of polytrauma rehabilitation is to sort through a long list of competing priorities. Should we prescribe a medication that helps reduce agitation even though it can make the patient less responsive? Should we go ahead and repair a skull defect surgically, or should we wait to allow rehabilitation gains to become more stable? Should we order a high tech prosthetic limb, or should we wait to see how far the patient progresses in cognitive rehabilitation? These questions arise again and again, and the answers vary according to each individual's needs.

The multiple problems that these patients present require medical balancing acts and unusual cooperation across departments in the medical center. Polytrauma becomes the business of the whole facility that houses the program as it requires drawing on extraordinary medical and therapeutic expertise for each patient. The medical challenges may often be daunting, but the real focus at the PRCs is rehabilitation. Even as doctors battle to stabilize electrical brain activity or body chemistry, patients start relearning to eat, talk, focus their thoughts, and to walk or maneuver a wheelchair.

I met Sgt. Wade on the day of his admission at the Richmond PRC two years ago. He had just arrived by ambulance from Walter Reed Army Medical Center (WRAMC) and his parents and fiancé were eager to see the rehabilitation process begin. At 26, he had survived an Iraq car bombing that caused a fearsome combination of injuries-moderate-to-severe brain injuries, traumatic right arm amputation above the elbow, complex bone fractures in the right leg, and significant left visual field defect. He had a tracheostomy tube, feeding was by PEG tube, and initial evaluation showed severe-to-profound cognitive-communication impairments.

With his family's input and support from the interdisciplinary team, I developed a treatment plan that addressed restoration of oral feeding, removal of the tracheostomy tube, and establishment of a reliable system of communication for basic needs. Progress was steady, though not smooth due to difficulties related to Sgt. Wade's multiple medical problems and occasional emotional and behavioral complications that interfered with rehabilitation.

When Sgt. Wade left acute rehabilitation five months later, the feeding and tracheostomy tubes had been removed. He had learned to compensate for the left visual field defect and visual fixation, and was able to communicate using short sentences and was reading single sentences reliably. Writing remained a challenge because of the right dominant arm amputation, while memory and verbal reasoning tasks required moderate levels of assistance.

Treatment

At the VA, Speech-language pathologists and audiologists play an important role in the overall effort to provide the highest quality of care for the war wounded. As members of interdisciplinary inpatient and outpatient treatment teams at the four PRCs and at the 21 Polytrauma Network Sites currently under development throughout the VA system of health care, SLPs and audiologists deliver cutting-edge clinical services while working together to develop guidelines for best practices in the evaluation and treatment of complex and severe polytrauma sequelae.

Care for war-wounded patients is a high-priority and high-visibility effort in the VA. For the practice of speech-language pathology, it has aspects that are both rewarding and challenging. On the one hand, this is a young population, with a mean age of 28-educated, highly motivated, and with good family and community support, which all are good prognostic indicators for rehabilitation potential. At the same time, the VA is committed to supporting every effort to rehabilitate the combat-injured to their fullest potential. Challenges, on the other hand, are related to the complexity of injuries sustained that affect multiple organs and body parts with consequence for communication and cognition, including the brain, vision, hearing, facial trauma and disfigurement, emotional and behavioral problems, and upper extremity amputations. Additionally, the level of severity of impairments can range from mild to profound, which requires that SLPs have the technical skill and flexibility to treat conditions from minimal responsiveness to return to work or school.

At the PRCs, SLPs are members of the core polytrauma teams and have standing orders to assess cognitive-communication and swallowing functions within 24 to 48 hours of admission and then to treat the patients as indicated throughout their stay in rehabilitation. Initially, clinicians may participate in structured sensory stimulation, or may help establish basic communication, which could involve gestures or use of communication aids.

Swallowing and voice production are other important initial goals. As patients progress, SLPs begin to address functional communication, orientation to environment, attention, and memory skills. Behavioral issues, including agitation, aggression, and psychological trauma related to the war experience and adjustment to disabilities, may interfere with treatment plans at this stage of recovery. SLPs have to be knowledgeable about management of such problems and be able to work together with the treatment team, including the patient's family, to minimize their impact and duration.

With higher-level patients, speech-language treatment will concentrate on community and/or academic re-integration and may include goals related to pragmatics of verbal communication, attention and executive function skills, and compensatory strategies for organizational and memory problems using planners and electronic prosthetic devices.

Guidelines Underway

At the request of the VA Audiology and Speech-Language Pathology Field Advisory Board, clinicians from the PRCs and WRAMC have started working together to develop best practice guidelines for assessment and treatment of persons with polytrauma. In the past six months, these clinicians have been collecting information regarding principles and procedures for the assessment and treatment of polytrauma sequelae, including emergence from minimal responsiveness; functional communication; attention and memory disorders; problems with executive function, awareness, and pragmatics; visual impairments; prescription and training for assistive technology; and a model for comprehensive audiologic evaluation for polytrauma.

Results of this project will be disseminated to SLPs and audiologists working in the VA through upcoming professional conferences. These best practice guidelines, however, are relevant to SLPs and audiologists working in a variety of settings in communities throughout the country as the war injured return home and seek service beyond the VA and military treatment facilities.

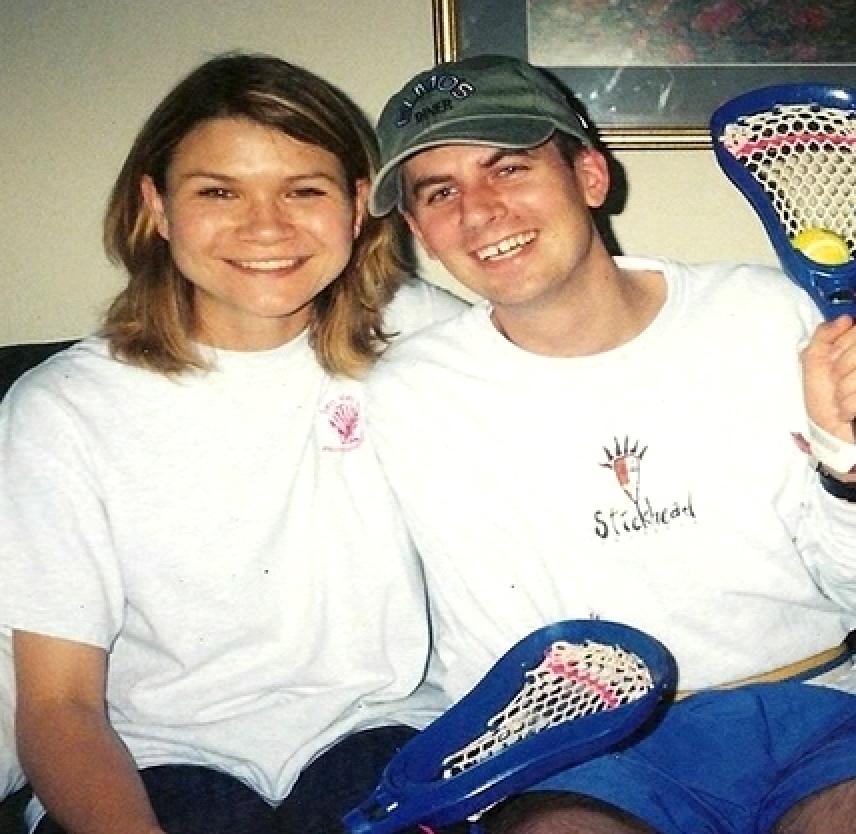

When patients leave the PRCs, 77% of them go home. Some are almost fully recovered, but for others swallowing may still be a milestone. When he was discharged from the Richmond PRC, Sgt. Wade had made remarkable progress, but a long road to recovery was still ahead. At first he spent a few months in rehabilitation in a VA long-term care program, after which he went home with Sarah. They were married last year and have made rehabilitation a family affair ever since. There is continued need for services which they receive at the local VA Medical Center, at WRAMC, and at a private facility in their community. They both feel that retired Sgt. Wade continues to make progress and that without rehabilitation progress might stall or even reverse.

Since our last phone call, Ted and Sarah Wade have returned from their ski trip with renewed energy and continued determination, believing their lives are a work in progress. The VA's PRCs also remain works in progress, sharing lessons with one another and with the major military hospitals by videoconferencing and by pushing clinical care to address the myriad, often invisible, effects of explosive blasts.

Micaela Cornis-Pop is a speech-language pathologist and Rehabilitation Planning Specialist in the VHA/PM&R Headquarters at the HH McGuire VAMC in Richmond, VA. Contact her at Micaela.Cornis-Pop@va.gov.

Cornis-Pop, Micaela. “A New Kind of Patient for Speech-Language Pathologists.” The ASHA Leader, 11(9), 6-7, 28. American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, 1 July 2006. Accessed 20 Jan. 2017. http://leader.pubs.asha.org/article.aspx?articleid=2278219.

© American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.