From the Preface

“I’m Okay”

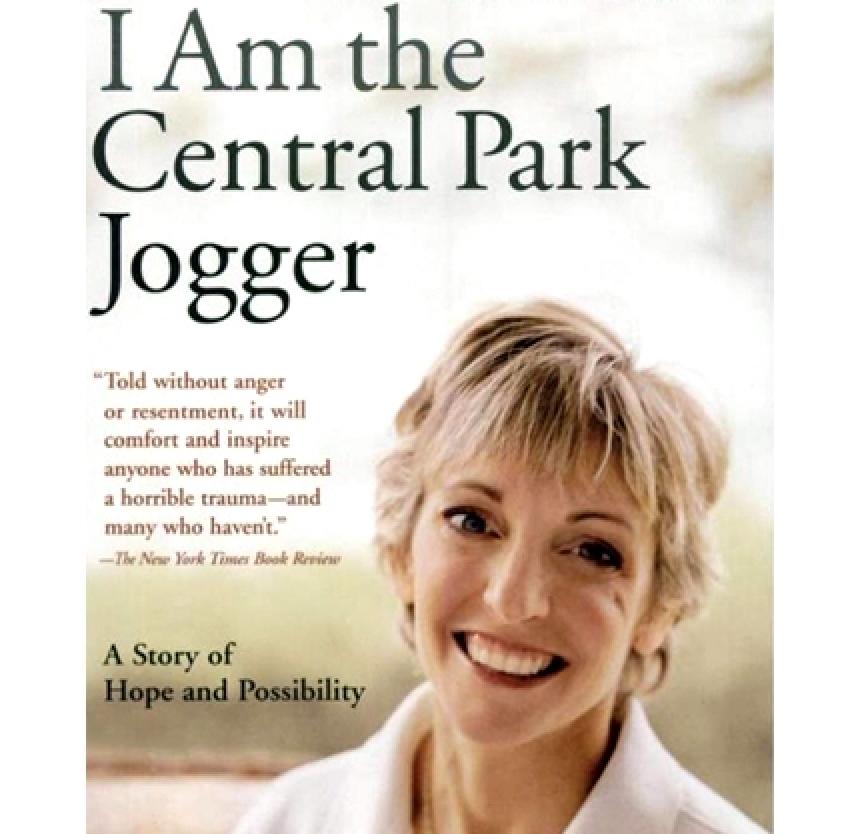

Shortly after 9 p.m. on April 19, 1989, a young woman, out for her run in New York’s Central Park, was bludgeoned, raped, sodomized, and beaten so savagely that doctors despaired for her life and a horrified nation cried out in pain and outrage.

I am that woman, until now known only as the Central Park Jogger, and this is my story.

From Chapter One

“Wilding”

At 5 p.m. on the day of the assault, I turned down a dinner invitation from a friend because I had too much work to do at the office. This was not unusual. At age twenty-eight, I was on the fast track at Salomon Brothers, one of the top-tier investment banks on Wall Street, and often worked late; it was one way to stay on the track.

Before I left the office, Pat Garrett, a colleague of mine who worked in the adjoining cubicle, asked my advice about a new stereo system. Three months earlier I had moved into a building on East 83rd Street and had bought a hi-fi that I had described to Pat as ideal for a smallish New York apartment.

“Why not come over and take a look at it?” I suggested.

“Sure,” he said, delighted. We had become good friends at Salomon, though our romantic attachments lay elsewhere.

“Come around ten. That’ll give me time to go for a run before you get there.”

There was no chance I’d forgo the run. I was obsessed with exercise and had run marathons in Boston and many 10K races in New York City. Since I normally arrived at work at seven-thirty, running in the morning would have meant getting up too early. Besides, a night jog was a fine way to relieve the stress of the day. I varied my route occasionally, as the mood struck me, but often, after entering Central Park on 84th Street, would turn north to the 102nd Street crossdrive. At night, this area of the park was secluded and dimly lit, but the only concession I made to its potential danger was to go there at the beginning of my run, rather than later at night. That friends had warned me about running alone at all at night may have goaded me to continue. I had been running there for two and a half years without their advice, and I didn’t need it now. Like many young people, I felt invincible. Nothing would happen to me. I can be determined, defiant, headstrong—and maybe there were deeper issues that drove me to take the risk.

“Great,” Pat said. “I’ll be there at ten.”

And while I remember the five-o’clock call, I don’t remember the conversation with Pat; I’ve reconstructed it here after later talks with him. Indeed, the dinner invitation is my last memory of anything—words, events, people, actions, touch, sights, pain, pleasure, emotions; anything—until nearly six weeks later.

Just before nine that night, a group of more than thirty teenagers gather on 110th Street, the northern end of Central Park, for a night of “wilding”—senseless violence performed because it’s “fun and something to do.”* They throw rocks and bottles at cars entering the park; punch, kick, and knock down a Hispanic man, drag him nearly unconscious into the bushes, pour beer over him, and steal his food. They decide not to attack a couple walking along the path because the two are on a date, but do go after a couple on a tandem bicycle, who manage to elude them. They split into smaller groups, then come together, then split again, like dancers in a sinister ballet. In all, eight are assaulted, including a forty-year-old teacher and ex-marine named John Loughlin, whom they beat unconscious.

Reports from that time allege that between eight and fifteen of them spot a young woman jogging alone along the 102nd Street crossdrive. There they tackle her, punch her, and hit her with a sharp object. Soon they drag her down into a ravine where one of the teenagers rips off her jogging pants. The woman is in excellent condition, and she kicks and scratches at them, screaming wildly; it is difficult to pin down her arms and legs. Finally, she is hit in the left side of the face with a brick or rock. Her eye socket shatters and she stops fighting and screaming.

By this time, John Loughlin, having regained consciousness, has been found by the police and reported his assault. He is taken to a hospital. The cops, now aware of the attacks from reports by some of the victims, have fanned out, looking for the assailants. The park goes quiet.

Three and a half hours later, two policemen, Robert Calaman and Joseph Walsh, sitting in an unmarked car at the 102nd Street crossdrive, are approached by two Latino men, shouting excitedly about a man in the woods who has been beaten and tied up. The policemen drive closer to investigate. Walsh gets out of the car and sees a body in the mud off the pavement, lying faceup and thrashing violently.

The men were wrong. It is the body of a woman. Naked except for her bra, which has been pushed above her breasts; her running shirt has been used to gag her and tie her hands in a praying position in front of her face. Walsh tells her he’s a policeman.

“Who did this to you?” he asks. “Can you speak to me?”

There is no response. She is bleeding profusely. One of her eyes is puffed out, almost closed. The policemen call an ambulance. EMTs arrive. She is taken to Metropolitan Hospital, known for its acute-trauma care, and rushed to the emergency room. She is met by Dr. Isaac Sapozhnikov, attending physician in the ER, who instantly calls Dr. Robert S. Kurtz, director of Surgical Intensive Care, at his home. Dr. Kurtz issues instructions for the immediate care the Jogger needs and comes in early that morning. He will supervise her treatment for the seven weeks she is at Metropolitan.

It is astonishing that the Jogger is alive. She is in deep shock, her blood pressure so low that the ER staff are unable to get an accurate reading. Her body temperature is eighty-five degrees, and she is unable to breathe on her own. A technician stands by her side to pump oxygen down a tube in her throat. Last rites are administered.

The woman is bleeding from five deep cuts across her forehead and scalp; patients who lose this much blood are generally dead. Her skull has been fractured, and her eye will later have to be put back in its place. When it comes time for surgery, Kurtz will be surrounded by a crackerjack team: two plastic surgeons, an expert on severe injuries to the eye; an ear, nose, and throat specialist. But for now, he—and Dr. Sapozhnikov before him—has only the emergency room staff to assist him.

The victim’s arms and legs are flailing violently, the aftereffects of massive brain damage, and that night have had to be tied to the gurney since there are not enough night nurses to monitor her constantly. The jerking and thrashing mean that both halves of her brain have lost their ability to control the movement of her extremities, to say nothing of her ability to think or feel. Many will stand by her bed in coming days and interpret this as the Jogger still fighting for her life.

There is extreme swelling of the brain caused by the blows to the head. The probable result is intellectual, physical, and emotional incapacity, if not death. Permanent brain damage seems inevitable.

As promised, Pat gets to Trisha’s apartment building at ten. He rings up. No answer. Funny, he thinks, she must still be in the shower. He waits, rings again. When there’s no response, he goes to a phone booth at the corner and calls her. He gets her machine. “Hi, I’m not able to answer the phone right now, but if you’ll leave your name and number . . .”

“Trisha, where are you? It’s the story of my life, women always standing me up,” he jokes. “I’m going home. Hope everything’s okay.” A tendril of worry takes root, grows. How could she have forgotten that they were supposed to meet? He calls Trisha’s former boyfriend, Paul Raphael, since Paul and Trisha often ran together. Paul doesn’t know where she is either. Pat considers calling the police, but doesn’t, thinking they’d laugh at him. It’s a regret he carries to this day.

Trisha is usually the first one in the office, so when Pat gets in around eight the next morning and doesn’t see her, the alarm bell rings more loudly in his brain. He asks Joanne, Trisha’s secretary, if she might be traveling. No, Joanne answers. His concern mounts.

Meanwhile, Peter Vermylen, a more senior member of Salomon’s Energy and Chemicals Group, and one of the people who has strongly warned Trisha against running in the park at night, is driving from his home in New Jersey to the PATH train that will take him to New York City. On the way, he listens to a radio report so disturbing that when he gets to the parking lot, he stays in his car until it finishes. A young woman has been attacked in Central Park, and he knows that Trisha jogs there almost every night.

He reaches Salomon Brothers and looks toward Trisha’s desk. It is empty. She usually gets in before he does, he thinks. He asks Joanne if she has heard from Trisha. She says no. He asks her to call Trisha’s apartment. No answer. Deeply worried now, he decides to contact the police, and after a couple of unproductive calls he reaches the precinct where a group of detectives have been assigned to the case. He tells the detective who answers the phone that he might know the victim and gives him Trisha’s name, age, occupation. The detective describes the victim’s hair as curly and medium brown, and Peter feels reassured: Trisha’s is dirty blond and straight. But then the detective asks if the woman wears a “distinctive piece of jewelry.” Peter puts his hand over the mouthpiece and asks Joanne about it. She describes it to him—it is a gold ring shaped into a bow—and he passes the information to the detective. “It’s her,” the detective says, and Peter hears him call to his colleagues, “We’ve got her. She’s an investment banker.” He asks Peter additional questions, but Peter can’t talk. He’s gasping for breath.

He calls Terry Connelly in Administration with the news. The detectives want someone from the firm to go to the hospital to identify the victim, and Peter volunteers for the job. No, Terry says, he’ll go himself, along with a close friend of Trisha’s, Pat Garrett. Peter tells him about the ring.

Pat and Terry go together to Metropolitan Hospital. They’re stopped by a security guard in the lobby. The place is a madhouse. Cops are everywhere. Reporters clamor for access and information.

“No one’s allowed up,” the guard tells them.

“But I’m here to identify her,” Pat insists.

“We’ll show you a picture.”

It’s impossible to identify the woman in the picture; her face is unrecognizable. Pat insists on seeing Trisha in person. His reason tells him the woman in the photograph with her battered body, swollen face, and puffy eyes is Trisha. But emotionally, he’s not prepared to say, “Yeah, that’s her.”

Reluctantly, a policeman escorts the two men upstairs. There is a guard outside Trisha’s door, and a small group of doctors and nurses whispering nearby. Otherwise, silence. Pat opens the door, looks down at the figure on the bed. The woman’s head is covered by bandages. Her face is so badly beaten and swollen it looks like some grotesque Halloween mask, barely human. Pat can’t believe that the body before him is alive. He’s still not positive it is his dear friend who is lying in front of him. A policeman enters, shows him the ring the victim wore—and Pat’s heart breaks. It is a little golden bow.

Pat calls the office to ask Joanne for numbers from Trisha’s Rolodex and embarks on one of the most difficult jobs he’s ever had to do: he must break the news to Trisha’s family.

The cops have been busy. Acting on tips and interviews, they have soon winnowed out suspects from the group allegedly in the park, among them Steve Lopez, fifteen; Antron McCray, fifteen; Raymond Santana, fourteen; Yusef Salaam, fifteen; Kevin Richardson, fourteen; and Kharey Wise, sixteen. They are black and Hispanic. Some live in Schomburg Plaza, a government-subsidized housing development directly north of Central Park, others in the Taft Houses project on Madison Avenue. Most are from two-parent, blue-collar environments. Nothing in their outward circumstances would mark them as capable of this violence. When two are put into Rikers Island prison, they are beaten by other inmates furious at the nature of their alleged crime.

On April 20, Elizabeth Lederer, one of New York’s top prosecutors and a renowned trial attorney, is assigned to the Jogger case by Linda Fairstein, head of the Sex Crimes Prosecution Unit; it has been put in Fairstein’s department because technically this is a sex crime, not yet a homicide. Lederer, already alerted that she will be the lead prosecutor in the case, goes to the 20th Precinct on West 82nd Street at 8 p.m. The investigation has been moved here from the much smaller Central Park station house, where some of the teens were initially taken and interrogated by detectives for hours. Primed by the police, Lederer spends the rest of the night of the twentieth and day of the twenty-first getting on videotape most of the suspects’ individual responses to her questions about the attack. The parents of some are there for the questioning, as is usually required for suspects under the age of sixteen, since otherwise what they say may not be admissible as evidence in a trial.

Some of the teenagers are arrogant and hostile; some are more subdued. Some admit to being part of the group who assailed the jogger; one—Wise—tells Lederer “this is my first rape.” Later, confessions will be recanted and the defense will argue that they were coerced. Though divergent in many respects, and though no clear physical evidence links the teens to the crime, the stories have enough similarities in their details to convince Lederer they are true. At the same time they point blame in so many different directions that she knows the task of putting together a solid, irrefutable scenario of the events of April 19 to present to a jury will be Herculean.

The media goes into a frenzy. New York City in 1989, as New York Times columnist Bob Herbert later describes it, is “a city soaked in the blood of crime victims. Rapists, muggers, and other violent criminals seemed to roam the city at will. . . . Someone was murdered every four or five hours.” The “Jogger case” speaks to the city’s worst fears, its deepest divisions, and indeed the nation’s fears and divisions. The major national stories that have occupied the press—the spread of the spill of oil from the Exxon Valdes, the closing arguments in the Iran/contra trial, the scandal involving House Speaker Jim Wright—are pushed to the sidelines. Because the body wasn’t discovered until the early-morning hours of the twentieth, full morning newspaper coverage doesn’t begin until the twenty-first, though the afternoon papers already had the story. Once it starts, it doesn’t stop. It is the lead story on local and national television for many days, and the newspaper coverage is even more extensive. Beyond the papers in the immediate area, the story is picked up within days by the Boston Globe, San Francisco Chronicle, Los Angeles Times, Northern Virginia Daily, USA Today, Seattle Times, Detroit News, Pittsburgh Post Gazette, Houston Chronicle, Dallas Times Herald, and Milwaukee Journal, among others. The International Herald Tribune runs a long story on the Jogger, and the case is covered both in the Evening Standard of London and La Presse Étrangère in Lebanon. A special hospital spokesperson is assigned to brief the media first hourly, then daily. As soon as they can, weekly and monthly magazines feature the Jogger and/or her alleged assailants. All three major women’s magazines—Ladies’ Home Journal, Good Housekeeping, and McCall’s—have comprehensive coverage. In December, the Jogger is chosen as one of Glamour’s Women of the Year, and People magazine names her one of the Year’s Most Interesting People.

There is an unwritten law among journalists that names of rape victims are not to be revealed, and in this case only a few break the rule, notably the Amsterdam News, New York City’s leading African-American paper, which urges fairness for the teenagers. Sensationalist headlines are everywhere. The teens are described as a “Wolf Pack”; there is a strident call to bring back the death penalty. The fate of the victim has resonances that affect the hearts of the journalists themselves, and although many of them know her identity, their obvious empathy and sympathy keep them quiet.

Family and friends begin to arrive at the hospital, among them several Salomon employees including Kevin O’Reilly, the Jogger’s boyfriend at the time, though few at Salomon know this. When the Jogger’s aunt, Barbara Murphy, gets there from New Jersey, she is amazed to see “men in suits” clustered outside the victim’s room. Then one of the Jogger’s two brothers, Steve, thirty-two, a labor lawyer, hurries in. He lives in Hartford, Connecticut, and was the first person Pat Garrett called from Metropolitan after identifying the victim. The Jogger’s parents, Jack, a retired marketing manager at Westinghouse, and Jean, a homemaker, Republican committeewoman, and eight-year school director on the Upper St. Clair School Board, fly in from their home near Pittsburgh. Salomon sends a limousine to pick them up, but, not expecting one, they miss connections and take a cab to the hospital. The cab door is opened by a policeman who has been alerted to expect them, and he escorts them into the hospital.

The Jogger’s other brother, Bill, thirty-five, an assistant district attorney in Dallas, arrives from Texas. By the time he gets to his sister’s room, someone has cleared the surroundings of all but doctors, nurses, and family members. (Steve will later stand guard against reporters trying to worm their way into the waiting room or overhear conversations in the corridor; one even disguises himself as an orderly and tries to get into the Jogger’s room that way.) Now the Jogger’s closest relatives have each had a chance to look at her. Gathered in the visitors’ waiting room, they grasp the extent of the tragedy. The sporadic movements of the Jogger’s arms and legs are her only signs of life. Her face is unrecognizable, even to them. That night, one family member asks the doctors to remove the restraints, but is told it’s too dangerous. She might hurt herself or pull out one of the many tubes—for breathing, for food, for elimination, for the monitoring of heart and other functions. Salomon will pay for full-time private nurses to attend her.

The family members meet in a conference room, where they are visited by Dr. Kurtz. He is not reassuring. They will set up a round-the-clock vigil at her bedside, in eight-hour shifts, until—they dare not finish the sentence. Day after day passes, and their beloved Trisha is still comatose.

New York City itself goes into mourning. The rape of a slim, seemingly frail, innocent woman—she weighs less than one hundred pounds—seems a rape of the city itself, and her fate becomes the major topic of discussion in every borough, every community. Some call her foolish for venturing into the park at night, but New York Times columnist Tom Wicker affirms in her “the primacy of freedom over fear—all honor to her for that.” Mayor Ed Koch, who has offered Trisha’s parents lodging at Gracie Mansion (they refuse), calls for a day of prayer, and churches, synagogues, and mosques hold special services. Many in the black community are defensive, warning that those in custody might be unjustly accused. Others are sympathetic. Neighbors of the suspects hold a prayer vigil outside the hospital. Members of four of the suspects’ families send flowers and express their grief.

Metropolitan Hospital is besieged by strangers wishing to help in any way they can, and a separate location is set up where blood can be donated to replenish that given to the Jogger. Salomon sets up a blood-donation center for its employees as well. The hospital switchboard is overwhelmed by calls asking for information about the Jogger’s condition or simply conveying good wishes and prayers for her recovery. Flowers pour in from all over the country, including eighteen roses from Frank Sinatra. None beyond the immediate family know that a doctor, though not Dr. Kurtz, has told them in a moment of particular brutality that “it might be better for all if Trisha died.”

The attack hits the people at Salomon Brothers particularly hard. John H. Gutfreund, chairman and chief executive officer, and Tom Strauss, president, were told immediately of the tragedy, and an attempt was made to keep the news from the employees until there could be more definitive word on the Jogger’s fate. This was futile, and on the first day the company is in shock. Gutfreund and Strauss go to the hospital, and soon many other Salomon employees are traveling to Metropolitan to pay their respects. Trisha has made a special effort to be friendly with her coworkers—reserve has long been a character trait and she has battled against it—and has succeeded. She is in fact loved, which adds heightened emotion to the suspense. Will she survive? her colleagues wonder. Will she ever wake from her coma?

On the twenty-first, a notice from Gutfreund goes to all employees:

There will be a service of prayer for the recovery of Trisha Ellen Meili at the Church of the Heavenly Rest, Fifth Avenue and 90th Street, tomorrow, Saturday, April 22, at 6:00 p.m. Please bring a candle.

Lisa Borowitz from the Corporate Communications Department is assigned to handle all calls coming into the firm regarding Trisha—for a while there are some two hundred a day. She will remain in that job for many months. And the company does much more. The Meili family has a comfortable income, but the medical bills, beyond Trisha’s insurance coverage, will be staggering. For starters, in addition to the cost of the private nurses, Salomon will also pay her hospital costs.

At first, the Jogger’s survival is the key issue. There is a terrible moment on April 27 when the breathing tube is removed and it is found the Jogger can’t breathe on her own—it’s the only time, Dr. Kurtz testifies at the trials of the defendants, that he felt like crying.

A second extubation is done on May 2; the crisis is resolved.

Still, questions about her eventual recovery haunt everyone. It is soon probable that the patient will survive, but in what condition? The worry revolves around the long-term damage to the brain. Will she be able to walk—let alone run—again? Once the eye is repaired and the socket rebuilt, how will her vision be affected? What about her fine-motor skills? Will she be able to fend for herself without assistance? Will she ever be able to live alone? What about her capacity for speech, for memory, for reasoning? No one knows or dares predict the outcome.

From I Am the Central Park Jogger by Trisha Meili. Copyright @2003 by Trisha E. Meili. Reprinted with permission of Scribner, an Imprint of Simon &Schuster, Inc. wwwsimonsays.com. For more information on Trisha Meili, go to http://centralparkjogger.com/about/index.cfm.